Perrin Technique for CFS/ME

North London Clinic

Perrin Technique London

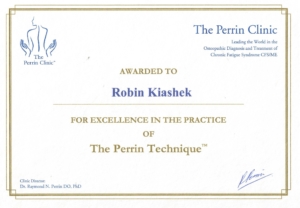

Licensed practitioner in The Perrin Technique for CFS/ME

Perrin Technique Practitioner in London, treating patients for CFS/ME and Fibromyalgia for over 10 years using The Perrin Technique.

Perrin Technique Practitioner in London, treating patients for CFS/ME and Fibromyalgia for over 10 years using The Perrin Technique.

The Perrin Technique™ is a manual method that aids the diagnosis (see The Theory below for evidence) and possible treatment of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ME (further research is planned in the NHS) and was developed by Osteopath and neuroscientist Dr Raymond Perrin DO PhD in 1989.

Certificate for Excellence awarded by Dr Perrin in the 2020 Perrin conference:

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) is a long-term illness with a wide range of symptoms. The condition is also referred to as ME, which stands for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. CFS/ME can affect anyone, including children. The main symptom is feeling extremely tired and generally unwell. But there are a variety of others that can vary in severity from day to day, or even within a day:

Symptoms of CFS/ME can be similar to the symptoms of some other illnesses, so it’s important to see a GP to rule out other issues.

Perrin Technique – The Theory

Evidence supporting the Perrin Technique

Prepared for The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

By The F.O.R. M.E. Charitable Trust -Registered Charity No 104500

NICE guideline: Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management stakeholder engagement workshop. London: Tuesday, January 16th 2018

A chance discovery in 1989 by osteopath and neuroscientist Dr Ray Perrin DO, PhD revealed a possible association between certain biophysical dysfunctions and the incidence of CFS/ME (Perrin 1993, Perrin, Edwards & Hartley, 1998). The concept of CFS/ME being primarily a physical disorder is still foreign to most of the medical profession. However, many recognise that CFS/ME has physical symptoms. There are physical components within the CDC criteria mentioned above which include sore throat, tender cervical or axillary lymph nodes, myalgia, and polyarthralgia (Fukuda et al, 1994).

The central nervous system is the only region in the body that was always believed to contain no true lymphatic vessels. The explanation for this has been that since the blood brain barrier (BBB) prevents large molecules entering the brain there is no need for lymphatic vessels in the CNS, as cerebral blood vessels will be adequate to drain the smaller molecular structures away.

However, hormones, which are large protein molecules continually enter the brain at the hypothalamus to enable the control of the endocrine system via the bio-feedback mechanism. Therefor the blood brain barrier even if undamaged is not as impenetrable as previously thought. The gaps in the BBB allow large toxic molecules to enter the brain such as heavy metals, bacterial infections and especially pro-inflammatory cytokines. So there has to be an alternate drainage system for the brain and spinal cord to remain in good health and if this drainage system is compromised illness ensues.

Cerebrospinal fluid has many functions, for example, as a protective buffer to the central nervous system and for supplying nutrients to the brain. However, one function has only received significant scientific attention in recent years, and that is the drainage of toxins out into the lymphatic system. As early as 1816 the Italian anatomist Paolo Mascagni speculated that there were lymphatic vessels at the surface of human brain (Mascagni and Bellini, 1816).

In man it was also hypothesised by some that CSF can leave the CNS via several routes. As in animal studies, these include pathways from the cranial and spinal subarachnoid space across the arachnoid villi to the dural sinuses and along the cranial, mostly via olfactory pathways through the cribriform perforations. There was evidence that there is further drainage down similar channels next to the cranial nerves especially the optic, auditory and trigeminal nerves in the eye, ear and cheek respectively and also down the spine outwards to pockets of lymphatic vessels running alongside the spine. (Zhang, Inman & Weller, 1990, Knopf & Cserr, 1995)

Perrin hypothesised that the neurolymphatic drainage becomes disturbed in CFS/ME due to dysfunctional noradrenergic sympathetic control specifically at the hypothalamus-locus coeruleus axis (Perrin, 2005).

In 2012 scientists at Rochester university in New York showed the first visible proof that CSF enters the parenchyma along the perivascular spaces that surround penetrating arteries and that some brain interstitial fluid is cleared along paravenous drainage pathways (Iliff et al. 2012).

As well as drainage into the sinus arachnoid villi there is further passage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) down the spine into the paravertebral lymphatics and alongside the I, II, V and VIII cranial nerves. The CSF then flows into the facial, cervical and eventually into the thoracic lymphatics. Most of the lymphatic fluid is then pumped into the blood by the sympathetic controlled, smooth muscle walls of thoracic duct via the left subclavian vein (Browse 1968, Kinmonth 1959).

Further studies on this drainage revealed it to occur mostly during delta wave sleep when the hypothalamus-locus coeruleus axis switches off (Xie et al. 2013). Delta wave sleep, which is the deep restorative sleep, is shown to be low at night in patients with CFS/ME who have high levels of non-restorative Alpha wave sleep (Van Hoof et al 2007). However, researchers at Stanford University in California have shown that in the day during the awake cycle there are high levels of delta wave in CFS/ME (Zinn & Zinn, 2013). The resultant drainage of toxins during the day would leave patients feeling fatigued and unwell. The increased activity at night of the hypothalamic-locus coeruleus axis at night prevents the healthy drainage and leaves patients in the state referred to as “Wired and Fired”. So, this region of the brain stem is of major significance in the pathophysiological process leading to CFS/ME as suggested by Perrin.

The existence of this neuro-lymphatic pathway has been further validated last year by a team in Virginia University in the USA. (Louveau, 2015) who discovered previously unknown lymphatic channels on the surface of the meninges and filmed the CSF flowing from the parenchyma of the brain into these lymphatic vessels via perivascular spaces.

Another group of neuroscientists in Finland published similar findings shortly after. (Aspenlund et al., 2015). The above pathway, together with a disturbance of spinal drainage of csf to paravertebral lymphatics, Perrin believes, is compromised as part of the common pathogenesis in CFS/ME (Perrin 2005, 2007).

In fact, not only is there visual evidence of the drainage system actual lymphatic vessels have been discovered in the membranes of the brain in both animal and human studies, which can now be visualized noninvasively by MRI scanning (Absinta, Ha et al. 2017))

If there is a minute buildup of intracranial lymphatic drainage, then one would expect a minor increase in intracranial pressure. This has been shown in a recent paper from researchers in Cambridge, where CFS/ME represents the most common and least severe presentation of idiopathic intracranial Hypertension (Higgins et al. 2017).

An earlier clinical trial on CFS/ME by Dr Perrin concluded that a major cause of the muscle fatigue is lack of lymphatic drainage of the muscle due to sympathetic dysfunction. This would lead to a excess of lactic acid among other metabolites in the muscles of CFS/ME patients (Perrin, Richards et al. 2011).

In 2013 researchers in Newcastle, UK showed, via arterial spin labelling, fMRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy, that disturbance in cerebral vascular control associated with sympathetic dysfunction is related to excess skeletal muscle lactic acid leading to the fatigue in CFS/ME.

If the overall lymphatic system and indeed neurolymphatic system is disturbed what toxins are we dealing with in CFS/ME.

The lymphatic system is there to drain away large molecular structures rather than small molecules which filtrate into the blood capillaries. The neuro-lymphatic system exists to drain large inflammatory or post infectious molecules such as cytokines and prostaglandins which may settle in the central nervous system following an infection or inflammation due to physical trauma. Recent studies in Stanford University have confirmed high levels of cytokines in the brain of CFS/ME patients with some such as Leptin correlating to symptom severity (Stringer et al. 2013). Environmental toxins can also become overloaded in CFS/ME such as heavy metals, petrochemicals and organophosphates, but a major source of neurotoxicity comes from an overstimulation of neuropeptides due to mental and emotional stress.

The Perrin technique is a system of manual diagnosis and treatment that is based on the hypothesis that CFS/ME is a disorder of the lymphatic drainage of the CNS, which leads to five physical signs shown in the diagram overleaf (Fig 6.) (Perrin R. 2005,2007)

- SPINAL MECHANICS AND DRAINAGE.

There is also a network of perivascular spaces down the spine that aids drainage of CSF to the paravertebral lymphatics, and besides Perrin’s work there has been some robust research done by one of the leading CFS/ME specialists in the US Prof Peter Rowe MD, who runs the Pediatric CFS Clinic at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, Baltimore, MD. (Rowe PC et al 2014)

Examining 48 pairs of subjects: age (10-30) a research study by Rowe et al showed localised impairments of motion in limbs and spine and in a IACFS/ME conference when asked about mid thoracic flattening and stiffness?

“Yes, we also see this …. and it is usually associated to the hypermobility of the cervical and lumbar region” Peter Rowe MD.

Rowe’s research has also demonstrated a link between the mechanical dysfunction to autonomic disturbance found in CFS/ME (Rowe PC et al. 2014)

It is also significant that Stony Brook University have shown that the neuro-lymphatic drainage occurs more when the subject in side lying. The analysis showed consistently that glymphatic transport was most efficient in the lateral position when compared to the supine or prone positions showing the importance of spinal posture in the drainage of toxins from the central nervous system. (Lee et al 2015)

2: Varicose enlarged lymph vessels: Due to a reversal of the sympathetically controlled thoracic duct pump. (Browse NL, 1968)

CFS/ME patients present with a history of trauma, congenital and/or developmental problems affecting the cranium and spine (fig 7) which may also be familial. This is also associated with other physical evidence of sympathetic nervous system disturbance due to hypothalamic dysfunction. It leads to lymphatic pump reversal causing palpable engorged varicose enlarged megalymphatics and further central neurotoxicity via the perivascular spaces.

In CFS/ME it is these drainage pathways, both in the head and the spine, that are not working sufficiently, leading to a build-up of toxins within the central nervous system. The aetiology may be traumatic, congenital and may even be hereditary. If the structural integrity of the spine and brain are both affected leading to reduced drainage, the increased toxicity (often following a viral or bacterial infection) plus stress factors (physical, chemical, emotional, immunological and/or environmental) will lead to hypothalamic dysfunction and thus affect sympathetic control of the central lymphatic vessels (Kinmonth, 1982) causing further backflow and worsening toxicity in the CNS leading to the vicious circle that we eventually call CFS/ME.

One independent study has indeed verified one of physical findings by Perrin, namely a tender point in a specific region of the left breast (Puri et al 2011).

NB Varicose thoracic lymphatics are always palpable in CFS/ME. In this rare occasion they are clearly visible (Perrin R, 2005 & 2007)

3: Tenderness at Perrin’s Point:

The connection between peripheral somatic nociceptive afferent fibres and sympathetic nerves has been observed in pathological mechanisms (Janig, 1988).

Sympathetic influence has been noted via:

- Noradrenalin directly on peripheral afferent via alpha 1 adrenergic receptors.

- Noradrenalin exciting alpha 2 adrenergic receptors mediating the release of prostaglandins exciting the primary afferent fibre.

- Sympathetic and sensory fibres coupled electrically via synapses or the lesser known ephapses resulting in ‘cross talk’ along the axons themselves. (Gasser, 1955).

- Noradrenalin release may have local effects on blood flow, environment in skin enhancing activity.

While many autonomic nerves are purely sensory, certain primary afferent nerve fibres also have an efferent (and trophic) function. Sensory neurotoxins stimulate transmitters released at peripheral endings to produce vasodilation and smooth muscle contractility. Furthermore, they may have effects on the regional leukocytes and fibroblasts leading to what is known as “neurogenic inflammation”, with eventual stimulation of somatic afferent fibres causing pain (Mense, 2004). This may explain many of the more severe musculo-skeletal and sensory symptoms affecting the patient with CFS/ME. .

Fibromyalgia is viewed by many as a form of CFS/ME with widespread pain in all four quadrants being the principal symptom. New evidence from biopsy has revealed a major source of pain in fibromyalgia, is due to an increase in sympathetico-sensory innervation (Albrecht, 2013)

Dizziness, palpitations and orthostatic hypotension are common symptoms of CFS/ME and may relate to cardiac plexus dysfunction. We aso know due to the reversal of lymph flow and formation of varicose megalymphatics that the sympathetic control of the smooth muscle wall of the thoracic duct is disturbed.

Therefore, due to viscero-somatic crosstalk from dysfunctional sympathetic control of the thoracic duct and disturbed cardiac plexus, a hypersensitive region slightly lateral and superior to the left nipple develops. this tender spot (also known as Perrin’s point), has been already independently verified in a controlled trial (Puri et al.2011, Perrin & Tsaluchidu 2009, Perrin 2005 &2007,)

4: Tenderness of the Coeliac Plexus: In cases when there are abdominal symptoms such as IBS, lower thoracic, lumbar, pelvic or lower extremity pain, the coeliac plexus will become overactive and more sensitive due to similar reasons for Perrin’s point.

5: A disturbance in the regular cranial rhythmic impulse (CRI):

Central to the principles of osteopathy is the presence of a palpable cranial rhythmic impulse. The CRI is strongest along the spinal cord and around the brain and which is transmitted to the rest of the body. The average pulsation of this mechanism is between 7 and12 beats per min in health (Sutherland, Wales ed. 1990)

CSF has an intracranial rhythm equal to the average adult pulse rate (50-100 bpm). This wave via the neuro-lymphatic drainage pathways meets the lymphatic pump of the thoracic duct (4 bpm.) .2,3 producing a third (interference) wave of around 8-12 bpm which Dr. Perrin hypothesized.4 is the source of the Cranial Rhythmic Impulse (CRI) (Perrin 2005,2007)

Three separate studies (Perrin 1993,1998 & 2005) have revealed a disturbed CRI and evidence of a retrograde, congested lymphatic system in CFS/ME patients (Fig 7) compared with healthy norms and that both increase in the lymphatic drainage as well as a stronger more rhythmic CRI coinciding with improvement of symptoms, supporting the view that the neuro-lymphatic flow is one and the same as the CRI (Perrin, 2007). With a palpable loss of vitality, the severity of which is often related to the overall symptom picture.

Indeed, all the physical phenomena seen in CFS/ME can be understood when the pathophysiology of the disease is viewed as being neuro-lymphatic in origin with impaired drainage resulting in sympathetic dysfunction.

The diagnostic technique based on the present NICE guidelines is a not a perfect reference standard but is the best available to the NHS. However, following the first oral hearing on Tuesday 18th April 2006 of the Gibson Enquiry at the House of Commons, it was generally concluded by those present that an earlier diagnosis would usually lead to a better prognosis when treating CFS/ME. The published report from the Gibson Inquiry of Nov 2006, described The Perrin Technique as “a useful and empirical method which although unorthodox should not be dismissed as unscientific and that it required further research” (Gibson, 2006).

An independent parliamentary enquiry was formed last year by Dr Ian Gibson MP to examine the latest research and treatment of CFS/ME. The Gibson Enquiry committee which included two eminent physicians Lord Turnberg and Dr Richard Taylor MP concluded that the NHS clinics treatment of CBT, GET and pacing is useful in mild cases but may prove harmful for severe cases. At the initial meeting it was unanimously agreed that early diagnosis leading to an earlier treatment and management strategy was a major factor in improving the prognosis. Dr Taylor was interested in the physical diagnosis developed by Dr Perrin stating that it looked simple to implement and most importantly sounded inexpensive and should be further investigated.

In this respect a blind controlled study was carried out at Wrightington Hospital, Wigan involving 2 NHS Trusts in association with the University of Central Lancashire with the significant results showing “proof of concept” and was published on November 13th 2017 in the BMJ Open. (Hives L et al, 2017)

CFS/ME is very much a biomechanical disorder with clear and diagnosable physical signs. This leads to central nervous system dysfunction that affects many, if not all metabolic pathways with each individual patient presenting slightly different biochemical disturbances leading to many subgroups when viewing the symptomatology and disruption of pathophysiological mechanisms.

The processes discussed above lead not only to the development of signs that have now been shown to be a valuable aid in the diagnosis but also support the use of The Perrin Technique as an integral part of the management and treatment programme of CFS/ME.

The Perrin Technique treatment protocol is combination of gentle cranial osteopathic treatment together with specific lymphatic drainage and spinal articulatory techniques to improve drainage of the toxins away from the central nervous system This in turn reduces the strain on the autonomic nervous system, which aids a return to good health.

In the first controlled trial into the treatment took place at Salford University in the 1990s. (Perrin, Edwards and Hartley 1998). The patient group were only given the Perrin technique. The members of a control group were selected from Action For ME via their national organisations members and completely anonymous to the research team to avoid any bias. All correspondence to the control group members was via Action For ME’s national offices in Wells, Somerset.

The new paradigm that Professor Edwards decided upon was very simple. Give more of a placebo to the control group by allowing them to choose any treatment that they wished to get better. So the choice was totally with the control group, as long as it did not include any manual therapy, and in the1990’s there was no evidence at all that manual therapy would help the many symptoms of CFS/ME.

The patient group were selected on a first come first served basis which does involve some randomisation. In other words, without exception, the first 40 volunteers who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were selected to be on the patient group.

Phase 1 of the research trials included self-report questionnaires to examine overall symptom change. With post-exercise fatigue being a major symptom of CFS/ME, the treatment protocol was best evaluated by determining its effects on muscle function which was analysed utilising isometric testing of the knee extensor muscles measuring the impulse torque.

The second trial, which included the same self-report questionnaires assessing symptom relief as in the initial trial, was divided into two parallel phases. Phase 2 primarily took the form of brain analysis using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to confirm if brain abnormalities seen in previous research were found in sufferers of CFS/ME. Central lymph scans were also carried out showing a possible trend of enlargement in CFS/ME sufferers. In the other part, phase 3, isometric tests were repeated with more accurate equipment than in phase 1.

The objectives of this research were:

1 To determine whether spinal problems were related to the symptoms arising from CFS/ME.

2 To test if my method of osteopathic treatment reduced symptoms associated with CFS/ME compared with those of a matched control group, who received no such treatment.

3 To reveal the sustainability of any improvement by a year follow up study and to investigate the likely repeatability of the initial study thus strengthening the argument of a relationship between the set osteopathic procedure and the improvement in symptoms associated with CFS/ME.

4 To determine if there is a visible disease process in the brain that may be causing the symptoms of CFS/ME.

5 To determine if there is any intrinsic muscle disorder that may be causing the symptom of fatigue in CFS/ME.

The first stage of the research showed that the major symptoms associated with CFS/ME showed an average of 40% improvement in the treated group compared with an average worsening of 1% in the non-treated group. A follow up, a year after the end of the study showed that the improvement seen in the patient group was generally sustained. (Perrin RN, Edwards J and Hartley P. 1998)

2nd controlled trial: Muscle fatigue in CFS/ME and its response to a manual therapeutic approach: A pilot study

Torque X time, the impulse torque, measured in Newton metre seconds (Nms) for each member of the patient group before and after the year’s treatment was recorded. The difference and percentage change in impulse torque was calculated and is inversely proportional to the post exercise fatigue, thus the greater the percentage change the less the fatigue. This test was only carried out on the patient group as the control group members of phase 1 were completely anonymous to Dr. Perrin having been independently selected by Action for M.E. Also, the control group members were CFS/ME sufferers living throughout the UK. The task of bringing them to Salford for the tests to be carried out would have proved logistically too difficult and possibly stressful and potentially harmful to the subjects.

There were only five negative values with only one recording a statistically significant lower value of impulse torque after the year. All the other patients showed an increase in the impulse torque with some over 100% improved on their first score.

The mean results of the knee extensor fatiguability tests for all subjects in the patient group were statistically analysed using a paired t-test, comparing the impulse torque before and after the yearlong study.

The mean value at the beginning was 1791Nms and at the completion had risen significantly to 2266 Nms. The results of the paired t-test on the above data are shown in Table 1, where the null hypothesis was that the mean impulse torque /Nms of right knee during first 30 seconds of final push was the same for tests 1 and 2.

In the both stages of the research the patients muscle fatigue was shown using objective test to be significantly improved and in second stage of the trials it was concluded that muscle fatigue is of a functional nature rather than any recognisable untreatable muscle disease (Perrin et al 1998, Perrin, Richards et. 2011)

Independent Support

The treatment plan has already been validated by an independent published survey conducted by a local patient support group in the North West (Vernon, 2004). One hundred and fifty members of the Stockport M.E. support group answered questionnaires related to the services provided by NHS professionals and complementary practitioners.

One of the outcomes of this independent survey was a list of therapies that the group’s members found useful in managing their illness.

THERAPY / TREATMENT

Number of Patients Expressing a Preference

The Perrin Technique 28

Nutrition/ Allergy testing 21

M.E. specialist Dr Andy Wright (who recommends many forms of new treatments that have shown to help including Dr Perrin’s

manual approach). 16

Healing/ Reiki 15

Homeopathy 11

Remedial Yoga 11

Acupuncture 9

Meditation 9

Thyroid specialist 8

Counselling 7

Tai Chi 6

Herbalist 6

Aromatherapy 5

Massage 3

Alexander Technique 2

Bowen Technique 2

Results of Stockport ME patients support group survey on treatment therapies effective in their case:

listed in order of preference (Vernon, 2004)

Some of the 150 patients listed more than one treatment that they had found helpful. This explains why the total of all patient numbers in this table add up to 161.

The data suggests that although aromatherapy, massage, the Alexander and the Bowen techniques are also forms of therapy with the emphasis on the physical, they score the lowest ratings in the table compared to the Perrin Technique which scored the highest. So, the observed benefits are not achieved by the mere laying of hands by a sympathetic practitioner. The complete treatment approach required includes spinal, cranial and specialised lymphatic drainage techniques.

IN 2010 The ME Association has been behind probably the largest-ever British survey of opinion among people with ME/CFS and their carers about which treatments and therapies work for them and which don’t. The survey also shows what people with the illness want from their health and social care providers. They are contained in a 32-page report called ‘Managing my ME’, which was published by The ME Association on 27 May 2010. The survey, carried out online and through a paper questionnaire by the ME Association in the summer of 2008, attracted huge interest when the questionnaire was held open online for over four months. A total of 3,494 people answered the questions online. Another 723 completed the paper questionnaire after it was circulated with our quarterly ME Essential magazine.

The survey results were submitted to an inquiry into the state of NHS services for people with ME/CFS in England carried out by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on ME. Key findings from the MEA survey were inserted into the final APPG report.

In the survey, a table of 25 therapies tried by patients were listed by the percentage of people who improved.

Graded Exercise Therapy (GET) was listed as 24th with only 22.1% improved with significantly 56.5% worse.

CBT fared slightly better listed at 22nd with only 25.9% improved.

The Top 3 were:

1.Pacing: 71.2% improved

2.Meditation and relaxation: 53.7% improved

3.The Perrin Technique: 51.3% improved

These three are the main modes of management and treatment for CFS advocated by Dr Perrin (Perrin 2005, 2007).

However, a more integrated management programme is often necessary and coordinated by Perrin and colleagues utilising a combination of these three approaches and other disciplines including nutritional support, sleep hygiene advice, counselling and sometimes psychotherapy with added advice regarding supplements. In some cases, it may also be necessary to refer the patient back to their GP for prescribed medication regarding pain relief, sleep and other severe symptoms.

The Perrin Technique is not an alternative method to beat CFS/ME alone, even though some patients do respond fully without any other intervention. It should be viewed as a diagnostic and treatment technique to be used in conjunction with other methods that have shown some success. It should be included as part of an integrative approach as a proven aid to the diagnosis and a treatment technique that has helped to reduce symptoms of CFS/ME patients for almost 30 years.

References

Absinta, Ha et al. Human and nonhuman primate meninges harbor lymphatic vessels that can be visualized noninvasively by MRI, October 3, 2017 eLife: 10.7554/eLife.29738.

Acheson ED. 1959. The clinical syndrome variously called benign myalgic encephalomyelitis, Iceland disease and epidemic neuromyasthenia. Am J Med. Apr; 26(4):569-95.

Albrecht PJ et al. Excessive peptidergic sensory innervation of cutaneous arteriole-venule shunts (AVS) in the palmar glabrous skin of fibromyalgia patients: implications for widespread deep tissue pain and fatigue Pain Med. Jun 2013; 14(6):895-915

Aspenlund A et al. 2015, Journal of Experimental Medicine June 15:. 212 (7) 991-999

Browse NL. 1968. Response of lymphatics to sympathetic nerve stimulation. J. Physiol. (London) 19: 25.

Carruthers BM et al. ME/CFS: A Clinical Working Case Definition, Diagnostic and Treatment Protocols J CFS 2003; 11(1):7-115.

Collin SM, Crawley E, May MT, Sterne JA, Hollingworth W. 2011. The impact of CFS/ME on employment and productivity in the UK: a cross-sectional study based on the CFS/ME national outcomes database; UK CFS/ME National Outcomes Database. BMC Health Serv Res. Sep 15;11:217.

Cserr HF, Knopf PM. 1992. Cervical Lymphatics, the blood-brain barrier and immunoreactivity of the brain: a new view. Immunology Today. 13: 507-512.

Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. 1994. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Annals of Internal Medicine. Dec 15; 121, 12: 953-959.

Gasser HS. 1955. Properties of dorsal root undmedullated fibres on the two sides of the ganglion. Journal of General Physiology. 38: 709-728.

Gibson I, et al. 2006. Inquiry into the status of CFS/M.E. and research into the causes and treatment. Group on Scientific Research into M.E.

Harvey SB, Wessely S. 2009. Chronic fatigue syndrome: identifying zebras amongst the horses. BMC Med. Oct 12;7:58.

Higgins JNP,Pickard JD, Lever AM. Chronic fatigue syndrome and idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Different manifestations of the same disorder of intracranial pressure? Med Hypotheses. 2017 Aug;105:6-9. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.06.014. Epub 2017 Jun 24.

Holmes GP, Kaplan JE, Gantz NM, Komaroff AL, Schonberger LB, Straus SE, Jones JF, Dubois RE, Cunningham-Rundles C, Pahwa S. 1988. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a working case definition. Ann Intern Med. Mar; 108:387-9.

Hives L, Bradley A, Richards J, et al. Can physical assessment techniques aid diagnosis in people with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis? A diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ Open 2017;0:e017521. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2017-017521

Iliff J et al. 2012. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, including Amyloid Beta. Sci Transl Med; 4, 147ra111 (Aug)

Janig W. 1988. Pathophysiology of Nerve Following Mechanical Injury. In: Proceedings of the 5th World Congress on Pain. Dubner R, Gebhart GF, Bond MR (eds.). Elsevier, Amsterdam. pp. 89-108.

Kinmonth JB. 1959. Sharpey-Schafer. Manometry of Human Thoracic Duct. J. Physiol. London. 177: 41P.

Knopf PM, Cserr HF. 1995. Physiology and Immunology of lymphatic drainage of interstitial and cerebrospinal fluid from the brain. Neuropathology and applied Neurobiology. 21: 175-180.

Lee H et al. 2015. The Effect of body posture on brain glymphatic transport. Journal of Neuroscience..J Neurosci. Aug 5; 35(31): 11034–11044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1625-15.2015

Louveau A et al. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels, Nature 2015)

Mascagni, P., and G.B. Bellini 1816. Istoria Completa Dei Vasi Linfatici. Vol. II. Presso Eusebio Pacini e Figlio, Florence. 195 pp

Mense S. 2004 Neurobiological basis for the use of botulinum toxin in pain therapy. Neurol Feb; 251 Suppl 1:I1-7.

Perrin RN. 1993. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a review from the biomechanical perspective. British Osteopathic Journal. 11: 15-23.

Perrin RN, Edwards J, Hartley P. 1998. An evaluation of the effectiveness of osteopathic treatment on symptoms associated with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. A preliminary report. Journal of Medical Engineering and Technology. 22, 1: 1-13.

Perrin RN, 2005. The Involvement of Cerebrospinal Fluid and Lymphatic Drainage in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ME (PhD Thesis), University of Salford

Perrin RN. 2007. Lymphatic Drainage of the Neuraxis in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Hypothetical Model for the Cranial Rhythmic Impulse. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 107(06), 218-224.

Perrin RN , Tsaluchidu S. 2009 Integrating biological, psychological and sociocultural variables in myalgic encephalomyelitis: Onset, maintenance and treatment. Panminerva Medica 51(03) Suppl. 1, 88, Sept.

Perrin RN, Richards JD, Pentreath V, Percy DF , 2011, Muscle Fatigue in CFS/ME and its response to a manual therapeutic approach: A Pilot Study. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine,

Puri B et al. 2011. Increased tenderness in the left third intercostal space in adult patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis: a controlled study. J Int Med Res.;39(1):212-4

Ramsay AM, O’Sullivan E. 1956. Encephalomyelitis simulating poliomyelitis.

Lancet. May 26; 270, 6926: 761-764.

Richards J, Selfe J, Sutton C, Gaber T and Perrin R. 2015-2016

Examining the accuracy of a physical diagnostic technique For Chronic Fatigue

Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. REC reference 12/NW/0877

Rowe PC, Marden CL, Flaherty MA, Jasion SE, Cranston EM, Johns AS, Fan J, Fontaine KR, Violand RL. Impaired range of motion of limbs and spine in chronic fatigue syndrome

J Pediatr. 2014 Aug;165(2):360-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.04.051. Epub 2014 Jun 11.

Sutherland WG, 1990. Teachings in the Science of Osteopathy, Wales AL. (ed). Sutherland Cranial Teaching Foundation, Ft Worth, Texas

Still AT. 1902. The Philosophy and Mechanical Principles of Osteopathy, Hudson-Kimberly, Kansas City, Mo. p. 47.

Stringer E et al. 2013. Daily cytokine fluctuations, driven by leptin, are associated with fatigue severity in chronic fatigue syndrome: evidence of inflammatory pathology. Journal of Translational Medicine 2013, 11:93 http://www.translational-medicine.com/content/11/1/93

Van Hoof E, De Becker P, Lapp C, Cluydts R, De Meirleir K. 2007.Defining the occurrence and influence of alpha-delta sleep in chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med SciFeb;333(2):78-84.

Xie L et al. Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain. 2013

Science.; 342: 373-377

Zhang ET, Inman CBE, Weller RO, 1990 Interelationships of the pia mater and the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) spaces in the human cerebrum. J Anat.; 170: 111-123.

The Perrin Technique™

Robin is trained in The Perrin Technique™ and attends the annual Perrin conference to keep up to date with developments. There is more information on The Perrin Technique™ website.

North London Osteopath Clinic

In North London we treat patients from Finchley, Muswell Hill, Crouch End, Arnos Grove, Wood Green, Highgate and even further afield.